10 km from the Tijuana San Ysidro border lies the Canyon de Alacran or Scorpion’s Canyon, one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. There are no paved roads, the site is strewn with garbage, and there is a limited number of showers and toilets.

Pastor Gustavo Banda Aceves built his church here in 2009 and in 2016 converted it into a shelter for migrants. When the pandemic-era Title 42 was in place, the US had closed the doors to asylum seekers so migrants stayed long term up to 1500 at a time. There is no modern sewage system and few showers and toilets. Thanks to donations and aid from UCSD, the migrants have added new housing and have recently built a basketball court.

Within the refuge’s embrace, sustenance took shape in the form of three nourishing meals, lovingly prepared and graciously offered. The fragrance of frijoles, rice, and vegetables intertwined harmoniously, a symphony of sustenance that offered hope and strength to those who called this haven their home. It was within this realm of sustenance that my humble Spanish connected me to the souls who resided here—brave migrants hailing from the varied lands of Mexico, Honduras, Venezuela, and Haiti.

They spoke of their homelands, their voices adorned with a delicate blend of nostalgia and sorrow. From Mexico, they hailed predominantly from the states of Michoacán and Guerrero, regions plagued by violence and the haunting presence of organized crime. Their lives, touched by the cruel hand of fate, were endangered, forcing them to embark upon this arduous journey in search of safety and freedom.

Within the depths of their gaze, I witnessed the struggle, the weight of uncertainty that pressed upon their weary shoulders. Only a fortunate few possessed appointments on the CBP app, scattered across San Ysidro and Juarez, where they fervently hoped to plead for asylum. Yet, the majority languished in perpetual limbo, each dawn greeting them with renewed determination to secure an appointment. Alas, the fickle nature of the app, fraught with glitches and limited daily openings, conspired against their endeavors, adding further strain to their already burdened hearts.

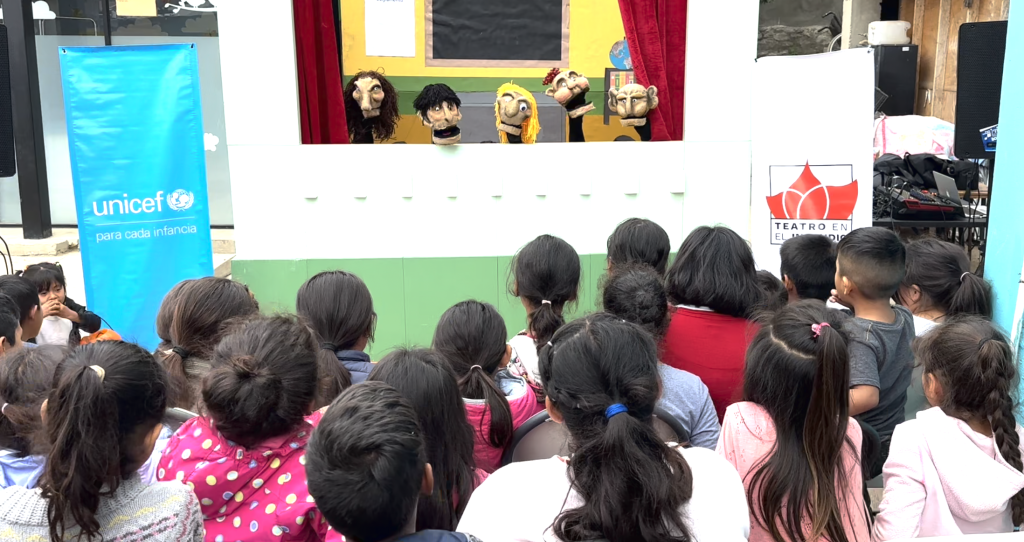

Amidst the tapestry of resilience and struggle, a serendipitous encounter awaited me as I roamed within the sanctum. The laughter of children, a harmonious symphony of innocent delight, drew me near. Enraptured, I stumbled upon a whimsical puppet show, sponsored by the guiding hand of UNICEF. The children, their spirits unburdened by the weight of the world, reveled in the embrace of joy, their laughter echoing through the canyon’s walls, weaving a tapestry of hope that transcended the boundaries of language and circumstance.

There are more migrant children in Mexico than in the past, and UNICEF is deeply concerned for the safety and well-being of each of them. These children have limited access to essential services they need for their well-being, including nutrition, education, psychosocial support, and healthcare. They are also at risk of exploitation, abuse and trafficking while on the road or amidst the crowded camps and respite centers at the border. Such difficult conditions come after they have fled violence, extortion, devastating poverty, and a lack of opportunity in their home countries of northern Central America. A child is a child first and foremost, regardless of their migration status.

Due to the large influx of Haitians after the earthquakes and continued tensions in their homeland, Little Haiti was born. In addition to a hostel, a kitchen, a store, a dining area, and a school were built. All the buildings are constructed by the labor of the migrants themselves, who have experience as bricklayers, plumbing, and electricity.

The UCSD-Alacrán Community Station was funded by the University of California at San Diego. Construction began at the end of 2019, right at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pastor Aceves says this project is different because shelters are usually temporary places to pass by on your way somewhere else.

This project from the beginning is different in that we allow families to stay until they have concluded their journey and can enter the United States. [pause strong] The timeframe for those who arrive in the community and stay is generally one-to-three years or longer.

Despite Border Patrol increasing the number of appointments to 1000 per day, thousands of migrants struggle to get an appointment each morning on the CBP app